Helpsheets ... continued 41 from homepage

Reaching agreement with HMRC

Reaching agreements with HMRC and how much the taxpayer can rely on them.

Businesses often have areas of uncertainty and write to HMRC to clarify the position; mostly, HMRC just refers the business to their published guidance. This policy is mostly unhelpful to businesses as they will have already read HMRC guidance but are still uncertain as to how it applies to their particular circumstances.

When a business manages to convince HMRC that they should provide a proper response to their query, HMRC sometimes provides a ‘non-statutory clearance’, where a business can demonstrate genuine uncertainty or inadequate guidance.

Even when a business obtains a non-statutory clearance, HMRC states that it is only its opinion and is not binding on any party. If the business considers the advice to be wrong, it can simply ignore it, but worryingly, HMRC does not consider itself to be bound by it either. If HMRC visits a business and considers the guidance given in the clearance to be wrong, it can impose its own interpretation of the law and assess the business for any VAT it considers due, even when the business has abided by the guidance in the clearance.

In theory, there is a ‘statement of practice’ where HMRC will abide by a previous ruling and only apply a new interpretation from a current date, but they often ignore this, and trying to enforce the statement of practice is very difficult.

In summary, in my view the non-statutory clearance procedure is not worth the paper it’s written on, and businesses cannot rely on it to provide certainty.

Formal agreements

Where there is a tax dispute between HMRC and the taxpayer, the parties can come to a formal agreement to resolve the matter. This could occur where the matter has been dealt with through the ‘alternative dispute resolution’ procedure, or where an agreement has been reached without it being formally decided by a tribunal.

In one case, HMRC reached an agreement with a taxpayer and then had second thoughts and tried to go back on the deal. As a result, HMRC issued an assessment, and the taxpayer appealed to the Tribunal (HMRC v Southern Cross Employment Agency Ltd [2015] UKUT 122 (TCC)). The taxpayer won at the First-tier Tribunal, but HMRC appealed the matter further to the Upper Tribunal. The taxpayer was once again successful.

HMRC argued that the legislation precluded it from entering into an agreement with the taxpayer in the particular circumstance of the case. It also considered that the agreement reached was ultra vires and therefore void; and finally, it disputed that it had ever actually reached a ‘compromise agreement’. However, both tribunals completely rejected all three of HMRC’s arguments.

This case has serious implications for HMRC and how it interacts with taxpayers. How could HMRC think it was right to reach a formal agreement with a taxpayer and then renege on it? Having done that, they not only forced the matter to a tribunal hearing but then appealed that decision and forced the taxpayer into prolonged uncertainty and a further costly tribunal hearing.

This is unfortunately quite typical of HMRC’s attitude to taxpayers. Even when it comes to an agreement with a taxpayer, it does not seem to consider itself bound by it and is prepared to act in a high-handed and unfair manner.

However, this case shows that if a taxpayer is prepared to stand its ground, it will have the support of the courts. Hopefully, HMRC will take note of this decision and stand by its agreements in future.

Practical tip

It can be difficult to get an agreement with HMRC and even then, it may not stand by it. However, if a business is prepared to stand up to HMRC, it should get the backing of the courts.

Claiming the employment allowance in 2025/26

Claiming the employment allowance in 2025/26 needs some extra care because legislation and payroll software specifications are conflicting.

The Autumn Budget 2024 and the December 2024 Employer Bulletin states that for paydays on and after 6 April 2025:

• the National Insurance Contribution (NICs) secondary (employer) threshold reduces from £9,100 to £5,000 per annum; and

• the rate of secondary NICs on earnings above the secondary threshold increases from 13.8% to 15%.

All of this will be legislated by an act of Parliament, currently progressing as the National Insurance Contributions (Secondary Class 1 Contributions) Bill. It is this legislation that also makes changes to the employment allowance:

• The value increases from £5,000 to £10,500 per annum; and

• The £100,000 eligibility threshold is removed.

Given the increase to employer costs as a result of the NICs increases, the incentive to claim the employment allowance is greater in 2025/26, especially as the removal of the £100,000 threshold opens this up to larger employers again.

Restrictions to claiming

The employment allowance indicator (field 166) is the one to use when making the annual claim for the employment allowance via the employer payment summary (EPS). In previous years, to be eligible for the allowance, employers would have had to indicate their business sector and confirm that de minimis state aid had not exceeded the maximum allowable over the last three years, as follows:

RTI Field Description Allowable state aid

199 Employer is in the agriculture sector. €20,000

200 Employer is in the fisheries and aquaculture sector €30,000

201 Employer is in the road transport sector €100,000

202 Employer is in the industrial/other sector €200,000

However, in its passage to Royal Assent, the National Insurance Contributions (Secondary Class 1 Contributions) Bill takes away any reference to receipt of EU state aid as an exception from claiming the allowance. This is the same legislation that removes the £100,000 NICs eligibility threshold, although it does not remove any other limitations such as connection and single-director companies. It is unfortunate that HMRC has not publicised the removal of the state aid restriction as widely as they have publicised the increase to the allowance value. In a display of disjointed thinking by civil servants, HMRC’s RTI specifications for 2025/26 have not removed the above RTI fields. Therefore, payroll software developer professionals will still have these in their products as they remain valid. However, whilst they remain valid together with the error messages that can occur when using them incorrectly, it is important that they are not used.

Communication is key

Consider the annual communication you have with clients. The £100,000 state aid and business sector eligibility references do not exist and there is no need to ask for this information. However, there is still a need for clients to identify they are eligible in all other respects

Making a claim for 2025/26

Eligibility remains a key factor, simplified in 2025/26 by the removal of some limitations. These limitations have, in my experience, resulted in confusion and have been a reason for not claiming the employment allowance at all. However, the increase from £5,000 to £10,500 and the fact it is open to more employers makes claiming worthwhile. Different software products will have different functionality, something HMRC recognises. In a communication to all developers dated 5 December 2024, HMRC advised that products should make the claims process simpler for employers by requesting the completion of only two fields on the EPS:

1. the employment allowance Indicator (field 166); and

2. ‘State aid rules do not apply to employer’ (field 203).

None of the above fields (199–202) should be used when making the claim for the employment allowance in 2025/26.

Practical tip

Talk with your software provider. Payroll software and legislation are at odds in 2025/26 when claiming the employment allowance. Talk to your provider and find out how they will facilitate claiming without the need for indicating the business sector.

Lifetime gifts in a nutshell

A look at what happens for tax purposes when making lifetime gifts.

The Oxford English dictionary defines a gift as: ‘something, the possession of which is transferred to another without the expectation or receipt of an equivalent’. The gift of an asset is thus not an arm’s length sale in return for market value proceeds, nor a loan or investment – it is entirely unilateral.

For capital gains tax (CGT) purposes, a gift is treated as a disposal alongside a sale; inheritance tax (IHT) only applies to gifts. For IHT purposes, lifetime gifting can be used to reduce the value of one’s estate upon death.

What is a gift?

When both the legal and beneficial ownership of an asset passes to the recipient, the transaction is complete. The beneficial ownership generally follows the legal ownership, and for a gift of land, that is the presumption (LPA 1925, s 60(3)); but for other assets, the beneficial ownership is presumed to remain with the donor unless that is rebutted by evidence that a gift was intended – this scenario is a ‘resulting trust’. Thus, when gifts of other assets are made, it is good advice to have some simple, informal evidence that a gift was the motive behind the transfer.

As well as gifts to an individual, gifts (or ‘settlements’) can be made into trust; although failure to properly establish an express trust will also lead to a resulting trust.

Gifts for tax purposes

Assuming that the beneficial ownership has been transferred to the recipient, there are tax consequences for both CGT and IHT purposes.

For CGT purposes, a disposal includes a gift with market value proceeds being deemed as received – this will result in a ‘dry’ tax charge, as CGT is payable even though there are no actual proceeds from which to pay it. Some assets are exempt from CGT – cash being a common example, along with machinery held for non-business use and one’s only or main residence. Holdover relief is available if the asset gifted is used in the donor’s trade – this defers the capital gain until it is sold by transferring the base cost to the UK-based recipient. Holdover relief is also available for any asset when an IHT charge arises – usually when placed into or leaving a trust.

For IHT purposes, the value of the gift is measured by the reduction of value in the donor’s estate. Once gifted or settled into trust, value only leaves their estate after seven years – should the donor die within that time the gift ‘fails’ and remains in their estate. When gifts are made to individuals, it is a potentially exempt transfer (PET), meaning there is no tax charge unless the donor dies within the next seven years. Any other gift (usually into trust) is a chargeable lifetime transfer, meaning there is an immediate IHT charge (measured against the available nil-rate band); after seven years, there would be no further charge. Should the donor die after three years, the tax rate on a failed gift is tapered down.

Reliefs are available for IHT purposes too. For lifetime gifts, there is an annual £3,000 exemption as well as a small gifts allowance of £250 to an unlimited number of people or in consideration of marriage. Agricultural and business property reliefs (APR or BPR) are available for lifetime gifts, as well as for a deceased’s estate upon death. Assets which qualify for these reliefs mean that the value of a gift is effectively nil; whilst these reliefs are unlimited, from April 2026, the limit is £1m per person. Under draft proposals within the Finance Bill 2024-25, a gift made before 30 October 2024 will qualify for unlimited APR or BPR if the gift fails; gifts made after 30 October 2024 will only attract unlimited relief if the donor dies before April 2026.

Practical tip

Gifts of assets other than land should accompany written confirmation that a gift was intended to ensure the beneficial ownership is transferred. Unless the asset is used in a trade, a gift to an individual will result in a CGT charge, as well as a potential IHT charge.

Doing up a main residence

Capital gains tax principal private residence relief could be forfeited should a main residence undergo refurbishment.

Principal private residence (PPR) relief is one of the more valuable reliefs against a charge to capital gains tax (CGT) on the sale of a residential property. The relief is available on an individual’s residence provided the house was occupied as their main residence throughout the period of ownership; the last nine months are also covered in the PPR claim. Furthermore, there are various provisions to cater for situations such as periods of absence.

Many taxpayers believe that if they have lived in the house as their main residence at any time, the entire period of residence and the last nine months are CGT-free. Whilst this may be true in most situations, there are conditions to the relief, one of which is that the property must not have been purchased ‘wholly or partly’ with the intention of making a profit (TCGA 1992, s 224(3)). Similarly, PPR relief is restricted if, after acquisition, expenditure is incurred ‘wholly or partly’ to make a gain on the sale. Therefore, any development and building profit arising from converting or reconstructing a PPR may be fully chargeable to CGT on sale; or it could be charged to income tax if the process is undertaken on a recurring basis.

‘Converting’ or ‘reconstructing’

‘Converting’ or ‘reconstructing’ a residence generally refers to substantial structural work being undertaken to significantly alter a property’s character, layout, or structure of a property which goes beyond repairs and maintenance. Reconstruction typically involves replacing major elements or completely redesigning parts of a building.

However, TCGA 1992, s 224(2) is written widely such that it could encompass improvements. ‘Improvements’ to a residence will cover alterations, enhancements, or additions to a property that increases its value, are permanent and are not merely repairs or maintenance. Improvements typically extend the property’s life, usefulness, or market value. They can include new features not previously present (e.g., adding a new bathroom or garage or possibly upgrading from single-glazed to double-glazed windows). Such alterations can be distinguished from regular repairs, which simply restore a property to its original condition without adding value.

Expenses on genuine improvements can be added to the acquisition cost of the property when calculating capital gains on sale. Routine maintenance or repairs (e.g., repainting, fixing a broken window) are not considered improvements and therefore cannot be included in CGT relief calculations (although should the property have been rented out at any time, such expenditure could be deducted from the income received).

There may be instances where the property is only being improved to sell or upgrade. In this case, proof will be required confirming that profit was not the main reason for undertaking the works, but that the property’s value increased during the improvement period.

Examples of refusal of PPR

HMRC has successfully argued that refurbishment activities indicated either a lack of genuine residence or that the property was intended for investment rather than as a main home. Increasingly, HMRC has won cases where the main reason for refusal was that the properties were uninhabitable before and during the refurbishments. A property must be liveable as a main home; therefore, should renovations make the property uninhabitable, HMRC may argue that the occupation was not genuine with the focus on ‘quality’ rather than length of occupation.

The case Gibson v HMRC [2013] UKFTT 636 (TC) underlines the importance of ‘quality’ of occupation. In that case, the taxpayer claimed his original intention had been to extend the property for a family home, but owing to the cost of alterations, he had instead ended up demolishing and rebuilding.

However, he subsequently had to sell the property, again for financial reasons. Prior to the sale he stayed in the property for four or five months, using very basic furniture. The First-tier Tribunal (FTT) found that the ‘quality’ of occupation was insufficient to make the property his sole or main residence and denied the relief. Again, the FTT looked at the degree of ‘permanence’ or expectation of ‘continuity’ of occupation and found there to be none.

Proving it’s a PPR

To prove to HMRC that the property could not be lived in during renovations without losing PPR relief, it needs to be demonstrated there was a genuine intent to occupy the property as the main residence before and after the renovations, as well as showing why living there was not possible during the works.

Keeping receipts and invoices from contractors for major work, especially for essential installations such as heating, plumbing, and electrics, shows that making the property habitable was the intention and priority. Registering the property as the official correspondence address for council tax and voting, even moving essential belongings into the property, can help to demonstrate commitment to the property as intending to be the main residence.

The case of Alison Clarke v HMRC [2014] UKFTT 949 (TC) shows how far HMRC will go to obtain confirmation that its refusal of PPR is valid. In that case, evidence from the local council confirming dates of occupation showed that the property was unoccupied for a long period. Gas bills indicated low consumption, the car had not been registered at the address for which PPR was being claimed, and the property was uninsured during the relevant periods.

How long to wait before selling?

Timing may be crucial if you have purchased a property requiring refurbishment and intend to make a PPR claim.

Ideally, the property must be fit to live in on purchase and you must actually reside in the property before, during and after undertaking the building works. On finishing the works, the longer the gap before selling the better.

Income tax implications

In some circumstances, the sale of a main residence property could be subject to income tax, rather than having CGT implications. Here we are looking at HMRC’s definition of a business as ‘an adventure in the nature of trade’ (see HMRC’s Business Income Manual at BIM2006).

HMRC invariably relies on this phrase to determine whether a transaction or series of transactions is taxable as trading income, even if the individual is not engaged in a trade in the usual sense.

For example, a property purchase or sale might be classified under this heading if there is evidence that the intention was to make a profit in a manner similar to trading. A high frequency of similar transactions, such as buying and selling multiple properties in a short period, can indicate trading. Should an individual have a history of similar transactions (e.g., buying a property, living in it for a period, renovating, living and then selling), HMRC would probably treat the property purchase as stock from the time it was clear that a ‘trade’ was being undertaken, and charge to income tax.

Builders, in particular, need to be careful when claiming PPR relief due to the specific nature of their activities as they often buy, renovate, and sell properties, which may lead HMRC to view all property transactions as ‘adventures in the nature of trade’.

Is being taxed under income tax so bad?

Should HMRC rule that a trade has taken place, this is not always a problem as some costs will be deductible from profit (e.g., finance costs should the renovations be undertaken using a bank loan).

In contrast, claiming financing costs to fund improvements, etc., as a CGT transaction deduction is not permitted.

Practical tip

Consistent evidence showing commitment to the property as the future home is crucial. Evidence of intent increases the likelihood of HMRC accepting that any temporary uninhabitable state during renovations was necessary and outside your control, allowing PPR relief to be retained.

Maximising PPR relief by moving back

How qualifying absences can reduce the capital gains tax bill on the sale of a former home.

If you have lived in a property at any point as your only or main residence, you may qualify for principal private residence (PPR) relief for certain periods during which you were not actually living in the property.

This can be particularly useful from a tax saving perspective, reducing the capital gains tax (CGT) payable on any gain realised on disposal.

Nature of PPR relief

PPR relief is a CGT relief, which means that you do not pay CGT on any gain that relates to a period for which a property was your only or main residence. A person can only have one ‘main’ residence for CGT purposes at any time, and married couples and civil partners can only have one main residence between them. Further, a property can only count as a main residence if it is actually occupied as a residence.

Occupying a property as an only or main residence opens the door to further periods of PPR relief.

Final nine months of ownership

Where a property has at some time been occupied as the owner’s only or main residence, the gain attributable to the last nine months of ownership qualifies for PPR relief regardless of whether the property is actually occupied as a main residence during that time.

This nine-month period is increased to 36 months where, at the time of the disposal, the owner is a disabled person or a long-term resident of a care home, as long as they do not own or have an interest in another residential property. In this context, a person is regarded as a long-term resident of a care home if they have been, or are expected to be, resident in a care home for at least three months.

Qualifying absences

Private residence relief is also available in respect of the gain relating to certain periods of absence. These include periods when the owner or their spouse was unable to occupy the property as their main residence because they were working elsewhere, and a limited period of absence for any reason.

Employment-related absences

Subject to certain conditions, the gain relating to the following periods of absence may qualify for PPR relief.

1. Any period of absence throughout which the individual, or their spouse or civil partner with whom they live, worked in an employment or office, all the duties of which were performed outside the UK.

2. Any period of absence not exceeding four years (or periods of absence which together do not exceed four years) throughout which the individual was prevented from living in the property because of the situation of their place of work, or because of a condition reasonably imposed by their employer requiring them to live elsewhere for the purposes of their employment in order to ensure that the duties of the employment are performed effectively.

3. Any period of absence not exceeding four years (or periods of absence which together did not exceed four years) in which the individual lived with a spouse or civil partner who was prevented from living in the property because of the situation of their place of work, or because of a condition reasonably imposed by their employer requiring them to live elsewhere for the purposes of their employment in order to ensure that the duties of their employment are performed effectively.

To access PPR relief for absences for these reasons, the individual must have occupied the property as their only or main residence prior to the absence. They must also occupy it after the period of absence as their only or main residence, unless they were prevented from doing so as a result of the situation of their place of work or that of their spouse or civil partner with whom they live or because of a condition reasonably imposed by the terms of their employment, or that of their spouse or civil partner with whom they live, to ensure the effective performance of the duties of their employment.

Absence for any reason

The legislation also allows the gain attributable to a period of absence for any reason not exceeding three years (or periods of absence which together do not exceed three years) to qualify for PPR relief as long as the owners lived in the property as a main residence before the period or periods of absence and after the absence.

This can be useful from a tax planning perspective, as moving into a former home as a main residence prior to disposal can potentially reduce the CGT payable on any gain.

The taxpayer can take benefit from both employment-related absences and other absences in relation to the same property.

Case study 1: In and out

Michael purchased a cottage for £300,000 on 1 January 2010. He lived in it as his main residence until 31 December 2015, after which it was let until 31 August 2022 while Michael was living with his girlfriend. After splitting up with his girlfriend, he moved back into the cottage for six months while waiting for his new home to be ready, moving into his new home on 1 March 2023. Michael let the cottage for a further year, selling it on 29 February 2024 for £480,000.

Michael owned the cottage from 1 January 2010 until 29 February 2024 – a period of 170 months. PPR relief is available as follows:

Period Occupation PPR No PPR

1.1.10-31.12.15 Only or main residence 72 months

1.1.15-31.12.18 3yr absence for any reason 36 months

1.1.18-31.8.22 Property let 44 months

1.9.22-28.2.23 Only or main residence 6 months

13.23-31.5.23 Property let 3 months

1.6.23-29.2.24 Last 9 months of ownership 9 months

170 months 123 months 47 months

123/170ths of the gain of £180,000 qualifies for PPR relief, equal to £130,235, leaving only £49,765 in charge.

Had Michael not moved back into the cottage, he would have lost relief for not only the period for which he lived in the property a second time, but he would also have not benefitted from the three-year period of absence for any reason. This would have reduced the period qualifying for PPR relief to 81 months (72 months of occupation as his only or main residence plus the last nine months), increasing the chargeable gain to £94,125. Assuming Michael had already used his annual exempt amount for 2023/24 and that he was a higher-rate taxpayer, moving back into the property saved him CGT of £12,420 (i.e., £44,360 at the 2023/24 residential rate of 28%).

Case study 2: Home and away

Joanna purchased a flat in Nottingham on 1 June 2016 for £180,000, which she lived in as her main residence until 31 October 2018. She is then sent to Paris to work by her employer. She lets out the property while she is away. She returns to the UK in March 2022, when she is sent by her employer to work in Edinburgh. She sells the flat on 31 May 2024 for £300,000, realising a gain of £120,000.

She owned the property for 8 years (96 months), of which she lived in it for 29 months as her main residence. As she was sent by her employer to work abroad and because of her work situation, was unable to return to occupy the flat as her main residence, she benefits from private residence relief for a further four years (48 months). As the property has been occupied as her main residence at some point, the last nine months’ gain also qualifies for PPR relief.

In total, PPR relief is available for the gain attributable to 86 months of ownership, leaving only that attributable to seven months (£8,750) in charge, of which £3,000 is sheltered by her annual CGT exempt amount.

Practical tip

Consider occupying a former home prior to sale to benefit from taking advantage of the ‘three year absence for any reason’ rule.

Have you used your capital gains tax annual exempt amount?

Individuals have a separate tax-free allowance for capital gains tax purposes – the capital gains tax annual exempt amount. Although it has been reduced considerably in recent years and is only £3,000 for 2024/25, making use of the allowance can still generate tax savings of up to £720.

The annual exempt amount applies to reduce the amount of net gains for the year on which capital gains tax is chargeable. The exempt amount is deducted from chargeable gains for the year after allowable losses for the year have been deducted, but before taking account of allowable losses brought forward from previous tax years.

Where a disposal is on the cards which may realise a chargeable gain, if the annual exempt amount for 2024/25 has not been used in full, making the disposal before the end of the 2024/25 tax year rather than after 5 April 2025may be beneficial as it will not eat into the 2025/26 annual exempt amount.

Before making the disposal, the size of the gain should also be taken into account. If the chargeable gain is less than £3,000 and the annual exempt amount is available in full, from a tax perspective, it will be beneficial to make the disposal in the 2024/25 tax year so as not to waste the 2025/26 annual exempt amount.

Spouses and civil partners

Spouses and civil partners each have their own annual exempt amount. Where one partner is planning to make a disposal, they should consider not only their available exempt amount, but also that of their spouse or civil partner. While spouses and civil partners cannot transfer their annual exempt amount to their partner, any transfers of assets between them are at a value that gives rise to neither a gain nor a loss. This means that by making a transfer of an asset or a share of an asset prior to disposal it is possible to utilise both partners’ annual exempt amounts.

Example

John and Julie are married. John wants to dispose of some shares which he expects to realise a gain of £2,700. As John has already used up his annual exempt amount for 2024/25, he is planning to wait until after 5 April 2025 to make the disposal, so that he can set his 2025/26 annual exempt amount against the gain.

However, Julie has not made any chargeable disposals in 2024/25 and her annual exempt amount for 2024/25 remains available. If John transfers the shares to Julie, taking advantage of the no gain/no loss rules, and she disposes of them before 6 April 2025, the gain will be sheltered by her 2024/25 annual exempt amount. By proceeding in this manner, Julie’s annual exempt amount for 2024/25 is not wasted, and both John and Julie have their annual exempt amounts for 2025/26 available to shelter disposals in that year.

Consider your marginal rate of tax

Chargeable gains are taxed at 18% where income and gains do not exceed the basic rate band and at 24% once the basic rate band has been used up. If the gain on a planned disposal will exceed the available annual exempt amount, it is necessary to take into consideration the rate at which the remainder of the gain will be taxed. Depending on the size of the gain, if the taxpayer is a higher rate taxpayer in 2024/25 but will be a basic rate taxpayer in 2025/26, it may be better to wait until 2025/26 to make the disposal, even if the annual exempt amount for 2024/25 is wasted. The aim is to minimise the tax payable on the gain, and there is no substitute for doing the sums.

Self-employed: What expenses can you deduct? Part 1

The rules governing whether an expense incurred by a self-employed trader can be deducted in calculating their taxable profit.

No one wants to pay more tax than they need to. However, this is exactly what will happen if you fail to take account of all allowable expenses in calculating your taxable profit. It is important, therefore, that as a self-employed trader, you keep accurate records of the expenses that you incur in running your business, and you also understand what can be deducted – and what cannot.

The general rule

The basic rule is that a deduction is allowed for expenses incurred wholly and exclusively for the purpose of the trade. This means that as long as an expense is incurred for the purposes of the business and only for that purpose, a deduction is given.

Unlike the rule governing the deductibility of employment expenses, there is no requirement for it to be necessary to incur the expense for it to be deductible.

No deduction for private expenses

Not surprisingly, you can only deduct business expenses when calculating your taxable profit – a deduction for private expenses is not permitted. To ensure that you can tell whether an expense is a business expense or a private expense it is advisable to have a separate business bank account and a separate business credit card and use these for all business expenses. The business bank account and credit card should not be used for private expenses.

When preparing your accounts, it is important to check that no private expenditure slips through the net – it is very easy to mix the two (e.g., picking up a magazine at the same time as buying some office stationery and paying for everything together with the business debit card). Here, a deduction is only allowed for the stationery; care should be taken to exclude the cost of the magazine. Any temptation to put private items ‘through the business’ should be avoided.

Mixed expenditure

Sometimes, expenses will be incurred for both business and private purposes. The fact that a deduction is not permitted for private expenditure does not preclude a deduction for the business portion, as long as it is possible to identify the different elements.

The legislation provides:

‘If an expense is incurred for more than one purpose, this section does not prohibit a deduction for any identifiable part or identifiable portion of the expense which is incurred wholly and exclusively for the purposes of the trade.’

Where an expense is incurred for both private and business purposes, the extent to which any deduction is permitted depends on whether it is possible to identify the business portion.

Expenses that have a business and private element should be apportioned and a deduction claimed for the business portion. The apportionment should be done on a just and reasonable basis.

This situation may arise if a mobile phone is used for both business and personal calls. From an itemised bill, it will be possible to determine which calls are business calls and which are private calls and to split the cost accordingly. For example, if the annual bill is £800 and 72% of the calls are business calls, a deduction of £576 (72% of £800) would be permitted.

As a sole trader, you may have one car which you use for both business journeys and privately. Here it is easier to keep a record of business mileage and to claim a deduction using the mileage rates under the simplified expenses system rather than trying to identify and apportion actual costs. Under this system, a deduction is allowed at the rate of 45 pence per mile for the first 10,000 business miles in the tax year, and at the rate of 25 pence per mile for subsequent business miles.

Planned changes to agricultural property relief

Protests by farmers following the October 2024 Budget have catapulted agricultural property relief (APR) into the spotlight. But what is the relief, who can benefit and how is it changing?

Nature of APR

APR and its companion relief, business property relief (BPR), are inheritance tax reliefs which reduce or eliminate the inheritance tax payable when qualifying assets are passed on, either during the transferor’s lifetime or on their death. There are two rates of relief – 100% and 50%.

APR is available in respect of land or pasture that is used to grow crops or to rear animals. It is also available in respect of:

- growing crops;

- stud farms for breeding and rearing horses;

- short rotation coppice – trees that are planted and harvested every ten years;

- land not currently being farmed under the habitat scheme;

- land not currently being farmed under a crop rotation scheme;

- the value of milk quotas associated with the land;

- some agricultural shares and securities; and

- farm buildings, farm cottages and farmhouses (which must be appropriate to the size of the farming activity taking place).

The property must be part of a working farm in the UK.

Farm equipment and machinery does not qualify (although this may benefit from BPR). Similarly, APR is not available in respect of derelict buildings, harvested crops, livestock or any property subject to a binding contract for sale.

To benefit from APR, the agricultural property must have been owned and occupied immediately before the transfer for at least two years if occupied by the owner, a company controlled by them or by their spouse or civil partner, or for at least seven years if occupied by someone else.

APR is given at the rate of 100% (so no inheritance tax is payable) if the person who owned the land farmed it themselves or if the land was used by someone else on a short-term grazing licence or let on a tenancy that began on or after 1 September 1995. In any other case, the relief is given at 50%.

Budget changes

A cap on the 100% rate of APR and BPR was announced in the October 2024 Budget. From 6 April 2026, the 100% rate will only be available on the first £1 million of combined agricultural and business property. Once this limit has been used up, agricultural and business property that would otherwise attract relief at 100% will instead only receive relief at 50% – an effective inheritance tax rate of 20%.

As APR and BPR are available in addition to the standard nil rate band of £325,000 and the residence nil rate band of £175,000 where a residence is left to a direct descendant, a couple can give away a farm worth £3 million before inheritance tax is payable (as long as neither leaves an estate valued at more than £2 million as this will reduce or eliminate the availability of the residence nil rate band).

Where the changes will expose the farm to a potential inheritance tax bill, it is advisable to take professional advice. Consideration could be given to passing on the farm earlier; there will be no inheritance tax to pay if the transferor survives seven years from the date of the gift. To avoid an immediate capital gains tax charge, gift hold-over relief can be claimed jointly by the transferor and transferee. Agricultural land which would not qualify for gift hold-over relief as a business asset qualifies if it counts as agricultural property for inheritance tax purposes. This will delay payment of the capital gains tax until the farm is sold.

Claiming tax relief for expenses online

Employees who incur expenses in undertaking their job may be able to claim tax relief for those expenses where they are not reimbursed by their employer. The expenses will qualify for relief if they are incurred wholly, exclusively and necessarily in the performance of the duties of their employment or meet the deductibility conditions for particular types of expenses, such as travel expenses or professional fees and subscriptions.

Last year, HMRC introduced new evidence requirements for claims for employment expenses. While the new rules were being implemented, they also closed their online expenses claim service for a limited period. During this time employees who wished to submit a claim for relief for employment expenses had to do so by post on form P87.

A new iForm went live in December, meaning employees can once again claim relief for employment expenses online.

Making an online claim

A claim can be made online using the new iForm by visiting the Gov.uk website at www.gov.uk/tax-relief-for-employees/travel-and-overnight-expenses, but only if the claim amounts to £2,500 or less in a single tax year.

Where the amount claimed is more than £2,500, it must be made in the tax return. Employees who are required to submit a Self Assessment tax return should make the claim in their return, even if it is for £2,500 or less.

Evidence required

Claims for tax relief for employment expenses must now be accompanied by evidence in support of the claim. The evidence that is required will depend on the nature of the claim.

For example, where the claim is for a subscription to a professional body, a receipt or other evidence of the amount paid to that body should be supplied. For mileage allowance claims, a mileage log should be maintained which shows each journey, the postcode for the start and end of the journey and the reason for the journey. The mileage log should be supplied with claims for mileage allowance relief.

Where an employee is required to work from home some or all of the time, a claim can be made for the additional household costs incurred as a result. Where such a claim is made, the claimant will need to submit a copy of their employment contract or such other document as makes it clear that the employee is required to work from home rather than working from home through personal choice.

For other expenses, a receipt or other evidence, such as a bank or credit card statement, must be provided which shows both the item in respect of which relief is claimed and also that the claimant paid for that item.

Evidence is not required for flat rate expenses claims made for uniforms, work clothing and tools.

What counts as agricultural property for APR?

Farmers have been hitting the headlines of late following the October 2024 Budget announcement that the rate of agricultural property relief and business property relief will be cut from April 2026 so that the 100% rate will only apply to the first £1 million of combined business and agricultural property from that date. In excess of this, the relief will be given at a rate of 50% – equivalent to an inheritance tax (IHT) charge of 20%. Farmers will continue to benefit from the nil rate band and residence nil rate band as for other taxpayers, meaning a couple can leave a farm worth up to £3 million free of IHT, as long as it includes a farmhouse worth at least £350,000 and neither partner’s estate is worth more than £2 million.

APR

Agricultural property relief (APR) is an IHT relief that allows agricultural property to be passed on free of IHT where the qualifying conditions are met. The relief applies where agricultural property is passed on during the individual’s lifetime or on their death.

The property must be part of a working farm in the UK that is owner occupied or let. The property must have been occupied for agricultural purposes immediately before the transfer for two years if occupied by the owner, a company controlled by them, or their spouse or civil partner, or for seven years if occupied by someone else.

Relief is given at the rate of 100% (subject to the cap applying from 6 April 2026 where the person who owned the land farmed it themselves, the land was used by someone else on a short-term grazing licence or it was let on a tenancy that commenced on or after 1 September 1995.

What counts as agricultural property?

For the purposes of APR, agricultural property is land or pasture that is used to grow crops or to rear animals. It also includes:

- growing crops;

- stud farms for breeding and rearing horses;

- short rotation coppice (trees that are planted and harvested at least every ten years);

- land currently not being farmed under the Habitat Scheme;

- land currently not being farmed under a crop rotation scheme;

- the value of milk quotas associated with the land;

- some agricultural shares and securities; and

- farm buildings, farm cottages and farmhouses.

It is important to note that to qualify for the relief, buildings must be of a size and nature appropriate to the farming activity. Farm cottages and the farmhouse must be occupied by someone employed in farming or by a retired farm worker or the spouse or civil partner of a deceased farm worker.

Buildings are valued on the basis of their use for agricultural purposes. Any value in excess of this, for example, as a country residence, does not qualify for APR.

Exclusions

Farm equipment, derelict buildings, harvested crops, livestock and any property subject to a binding contract for sale does not count as agricultural property, so does not qualify for APR. However, business property relief may apply where the associated conditions are met.

CGT main residence relief - Part 1

When does the ‘clock’ start? A recent capital gains tax case that seems to have upset HMRC. The relatively few sections of legislation starting at TCGA 1992 s 222, governing ‘only or main residence relief’ (commonly known as principal private residence (PPR) relief) have been the subject of numerous fierce debates over the years.

A series of cases culminating in a Court of Appeal hearing in 2019 has caused HMRC some serious introspection, followed by some sulky ‘reforms’ of the tax code (through FA 2020, s 24) that, despite ostensibly being aimed at making the regime fairer, somehow conspired to net around £150m per annum in additional tax revenue by 2023/24.

Unfortunately for HMRC, the adverse rulings just keep coming.

The legislation on ‘period of ownership’

The code basically starts by relieving any capital gain arising on the disposal of a dwelling house that has been a taxpayer’s PPR during their ‘period of ownership’. The relief is restricted according to various parameters, such as any periods where the dwelling house has not qualified as the taxpayer’s PPR during that period of ownership.

HMRC has long maintained that the ‘period of ownership’ commences immediately when the taxpayer acquires any interest on which expenditure might be deductible in computing a capital gain (see, for instance, HMRC’s Capital Gains Manual at CG64930).

For example, this could include acquiring an interest in the land on which a dwelling house is to be built later (or first acquiring a leasehold that is later enfranchised into the freehold).

However, HMRC has also insisted that only the period in which the PPR is physically occupied as the taxpayer’s main residence will qualify as their PPR. Following HMRC’s approach, if there is a significant delay between first ‘signing contracts’ and moving into the property, PPR relief will not cover that initial phase of the period of ownership.

Case law

HMRC’s position has been supported by case law, such as Henke v HMRC [2006] STC (SCD) 561, wherein a married couple purchased a bare plot of land in 1982 but did not build a house and start to live in it until around 1993. The Special Commissioner upheld HMRC’s argument that the first decade or so of the taxpayers’ period of ownership, starting with the purchase of the land, did not qualify for PPR relief, as they did not occupy a residence there until 1993.

However, in Higgins v HMRC [2017] UKFTT 236 (TC), a case involving a delay in taking up occupation of an off-plan apartment, the First Tier Tribunal decided that the four-year interval between the taxpayer entering into the contract in 2006 and the property being ready to move into around 2010, should not make up part of Mr Higgins’ overarching period of ownership, so as to dilute the PPR-qualifying period afterwards. Rather, his period of ownership began only when the purchase finally completed.

The case went against the taxpayer at the Upper Tribunal, but in Higgins v HMRC [2019] EWCA Civ 1860, the Court of Appeal agreed with the original ruling in favour of the taxpayer, noting:

• When contracts were exchanged in 2006, Mr. Higgins’ apartment (his dwelling house for PPR relief purposes) was no more than an empty space in the tower and did not physically exist until November 2009 at the earliest; and

• it would be illogical for the relief to be unable to fully cover people buying a new-build home and waiting some considerable time between signing contracts and completion or being able to move in.

The final ruling carried some weight as a Court of Appeal case, forcing HMRC into a bout of soulsearching. Amongst other things, this resulted in a new TCGA 1992, s 223ZA, which broadly set out that a delay of up to two years between acquiring an initial interest in the land and physical occupation of the dwelling would qualify for PPR relief. However, a greater delay in moving in would mean none of the interval would qualify for PPR relief – it should be treated as ‘all-or-nothing’. ... continued ...

Spreading the cost of selling your company – tax implications?

There comes a time in every business owner's life when retirement looms and thoughts turn to succession planning. Planning should ideally start two years before the date of disposal to preserve Business Asset Disposal Relief (BADR), if applicable, and optimise the timing of tax payments.

The most tax-efficient structure depends on the seller's goals:

- If the aim is to minimise risk and tax liability up front, a full cash sale (with BADR) is probably the best option.

- If deferment of capital gains tax (CGT) with spread payments is the aim, then loan notes should be considered.

- If it is felt that the company will grow, an earn-out can increase total proceeds but carries more risk.

BADR

To claim BADR, the company must be a trading company (or the holding company of a trading group) and the director shareholder must own at least 5% of the company’s ordinary shares for at least two years before sale.

Those shares must permit the shareholder to have at least 5% voting rights and :

entitlement to at least 5% of the profits available for distribution; and

5% of the distributable assets on a winding up of the company; and

5% of the proceeds in the event of a company sale.

BADR reduces the tax rate to 10% (increasing to 14% for 2025/26 and 18% for 2026/27) on qualifying business disposals, applying to the first £1 million of lifetime gains, and is therefore particularly beneficial for higher and additional rate taxpayers who otherwise would be taxed at 24%. However, should the gain exceed £1 million, any excess is taxed at the usual 24% CGT rate for higher and additional rate taxpayers only. Generally disposal will be of the whole business but it is possible to claim BADR on a partial sale. BADR must be claimed on or before the first anniversary of the 31 January following the tax year in which the disposal occurs.

Deferred Cash Consideration - When a company is sold with cash payments, HMRC treats the gain as taxable in the tax year of completion, i.e. instalment payments do not spread the CGT liability. Therefore, the seller may have to pay CGT by 31 January following the end of the tax year of sale, even though not all of the cash has been received. However, sellers can request HMRC to allow tax payments in instalments, provided these instalments are received over a period of at least 18 months and continue after the 31 January tax payment date.

Loan notes (deferred payments) - Accepting qualifying loan notes (e.g., unquoted company shares or corporate bonds – QCB) in all or part payment can enable the CGT to be deferred until the notes are redeemed or sold. BADR is normally lost as QCBs are not chargeable assets for CGT purposes (because the acquiring company will not be their ‘personal company’). Sellers will be liable to CGT on the deferred QCB gain at the prevailing tax rate in the tax year of repayment (when the CGT rate may or may not be higher than the current 24%).

However, an election can be made to trigger CGT immediately, allowing BADR to be claimed on the gain made, chargeable in the tax year of the share sale. Where an election is made, sellers must ensure they have sufficient funds from the deal to cover CGT on both cash and loan note considerations by 31 January following the tax year of sale.

If the loan notes are non-qualifying (e.g., redeemable within six months or bearing interest), any gain can be deferred so that it will crystallise when the security is redeemed or disposed of, or ceases to qualify as a security. However, no BADR can be claimed.

Earn-outs (contingent payments) - If part of the sale price depends on future business performance, CGT is initially calculated based on a reasonable estimate of those future earn-out payments. The additional cash to be received as an earn-out is considered an unascertainable amount and treated as a separate asset. BADR may still apply, but only to the portions of the gain meeting the criteria.

For example, the seller's company value increases by 10% in the year after sale, and the agreement states that the seller will receive a cash sum equal to 5% of the net profit after tax. This right to receive 5% of the profit has a value, eligible for BADR as consideration for the sale of trading company shares, taxed in the year of sale. However, when the additional cash gain is ultimately received, it will be considered a disposal of a ‘chose in action' (rather than the shares) and BADR will not be applicable.

If the earn-out is received in shares instead of cash, the gain may be rolled over, deferring CGT until those shares are sold.

Practical point - For married couples, consider transferring shares to your spouse before the sale; this action can double the £1 million BADR limit, provided the qualifying conditions are met.

Side hustle hints!

A reminder to those with secondary sources of online income that they may be subject to tax or National Insurance contributions liabilities.

Although it was originally recorded in use in the 1900s, the expression ‘side hustle’ has been increasingly used in the present century. Various definitions can be found, but generally this will be along the lines of an activity carried out for income to supplement that received from a main source.

One of the most popular means of generating additional income is by selling goods or services online through marketplaces such as eBay, Amazon, Etsy and others. Assuming their sales efforts are successful, an individual must then consider whether the income generated is subject to tax. This could potentially be income tax, capital gains tax (CGT) and if the £90,000 registration threshold for all sources is exceeded, value added tax (VAT).

Non-trading

There will be online sales that clearly will not be seen as trading – most commonly, this might be by selling unwanted items (e.g., clothing, ornaments, etc.), that have been owned for some time and were not purchased with a view to being sold. Although the profit (if there is any) from such sales – maybe after clearing the loft or garage – would not be subject to income tax, CGT could apply if more expensive items are sold.

Chattels (i.e., personal possessions) are exempt unless sold for more than £6,000, a limit that applies to single items and sets such as chess pieces, books by the same author or on the same subject or matching ornaments. Special rules apply in calculating the taxable gain for chattels.

Trading

Individuals who are buying, making or perhaps ‘upcycling’ items and then selling them online will potentially be subject to income tax and National Insurance contributions (NICs) in the same way as anyone carrying on a trade or profession. The same will apply to those providing a service they advertise online. HMRC gives examples of gardening and repairs, dog walking, taxi driving, delivering food, tutoring, babysitting and nannying, hiring out equipment, and creating online content. Once such activities are being done with a view to making a profit, it is likely that a trade is being carried on and HMRC may need to be advised, and a tax return completed.

There is a trading allowance of £1,000, which can be set against income from such activities, and if gross income is below that threshold, the sales do not have to be reported to HMRC. Above this amount, the allowance can be deducted from the gross income and tax and NICs paid on the excess as applicable. Instead of claiming the trading allowance, any expenses incurred wholly and exclusively in carrying on the activity can be deducted to calculate the taxable income. If a loss arises, it may be beneficial not to claim the allowance because the loss could be deducted from other income in calculating overall income tax liability.

Information disclosure

Since 1 January 2024, online marketplaces have been obliged to collect details of individuals and their sales activity, and this may be reported to HMRC if there are more than 30 sales in a calendar year which generate income of more than 2,000 euros (about £1,700). HMRC will be able to check this information against an individual’s tax return, and interest and penalties may be added to undeclared tax and NICs liabilities. On the plus side, the marketplace must provide the seller with a copy of the information that has been sent to HMRC so this should help with the preparation of a tax return.

In conclusion, income and expenses relating to online activities should be accurately recorded to determine whether and how there is a taxable profit to be declared.

Practical tip

As well as trading income, the principles above will also apply to income from land or property, such as renting a room or even the use of a driveway for parking, which may be done through an online platform.

Claiming rent-a-room relief - Part 1

The tax implications of renting a room to another family member such as a sibling.

Recent statistics show that in 2023, 28% of all young people aged 20 to 34 years were living at home with their parents. Whatever the scenario, having an extra adult in the household means extra costs such as increased utility bills, groceries, and other living expenses, leading many to pay rent.

That’s a relief

There are tax implications in doing so, although if the amount is kept under £7,500, the amount received may be covered by rent-a-room relief.

The rent-a-room relief scheme was introduced in the UK on 6 April 1997, its objectives being to increase the supply and variety of low cost accommodation, and labour mobility (e.g., enabling workers to use short-term accommodation to move around the country). In addition, by allowing individuals to earn tax-free income from letting out furnished accommodation in their main residence, HMRC’s administration has been reduced by simplifying the tax reporting requirements.

Over the years, the threshold has been updated, and as of the tax year 2023/24 (and 2024/25) it stands at a gross amount of £7,500 per year. A quirk in the rules allows more than two persons a share of the property income, with relief being set at £3,750 each.

Therefore, should three persons own (and live in) a property together and sub-let a room to a lodger, overall the relief is £11,250 (i.e., 3 x £3,750 relief). There are no National Insurance contributions levied on this income.

The relief is automatically applied, eliminating the need for a claim. The income limit covers all charges relating to the rental service, such as cleaning, laundry, or meals. This simplicity makes the relief accessible to a wide range of homeowners, including those running a bed-and-breakfast or a guest house.

Conditions for the relief

As ever with tax, there are conditions to be met.

The relief cannot be applied where:

• the room is let as office accommodation, a storeroom or a garage;

• the taxpayer is absent from the residence due to working overseas;

• the letting is to or by a company or partnership;

• the residence is permanently divided into two or more residences; or

• the property is buy-to-let, or a holiday let not also occupied by the landlord.

Note that the rules state that the room must be in a property that is the landlord’s main residence and as such, a claim could be possible should the landlord rent the property from another (although permission to sublet would be needed from the actual owner).

Rental income less than £7,500

If the rental income is less than the limit, the relief applies automatically, and there is no tax to pay or anything to report. If the sibling does not pay market rent but contributes to household expenses, it might not be considered as taxable rental income for the parents and, as such, non-declarable in any event.

However, if the rent charged is significantly below market rate, HMRC could consider the payment to be an informal gift rather than rent, which may trigger inheritance tax considerations in the future.

Rental income in excess of £7,500

The landlord can still benefit from the scheme should the rental income exceed £7,500 (or more than £3,750 per person where more than one person receives the income).

In this instance, tax is payable on the excess over the rent-a-room limit. This time, the relief is not automatic, and a claim is required via completion of a tax return. ... continued ...

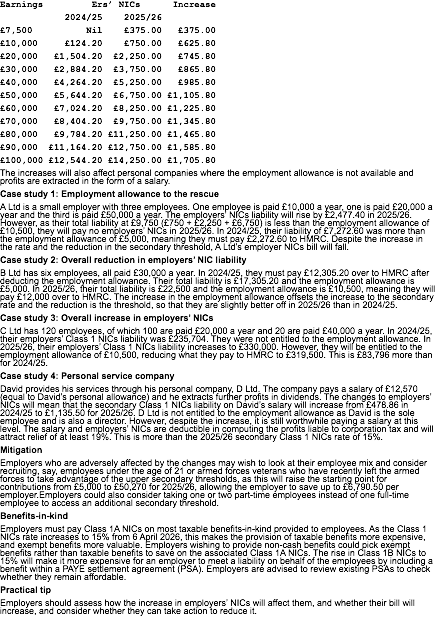

Going up: Employers’ NIC from April 2025 - Part 1

Time to disincorporate?

The impact of recent tax changes on profit withdrawal from small companies.

There are many factors to consider when deciding whether to run a business as a sole trader or via a limited company, but tax has always been a key one. Although there are some tax advantages of being unincorporated (e.g., the ability to carry back losses arising in the first four fiscal years of trade against other income, or lower National Insurance contributions (NICs) rates), the ability to choose when to draw income from a company (and are therefore taxable on it) and the option of taking mainly dividends (to avoid employer and employee NICs) has made the company option much more tax-efficient, particularly for businesses with high profits.

A shift in the tax landscape

Almost surreptitiously, this area has evolved over recent years to the extent that many smaller companies should be considering whether a limited company structure is still appropriate for them.

1. Since 1 April 2023, companies with profits above £50,000 have seen a significant increase in their marginal corporation tax rate, from 19% to 26.5%, until profits reach £250,000 when the main rate of 25% kicks in. These profit limits are reduced where there are associated companies. Although you only need to go back to 2017 for the last time we had differential corporation tax rates, the threshold at which the small profits rate was payable was much higher at £300,000, so many more companies than in the past are affected by the increase.

2. Employers’ NICs are to increase significantly from 6 April 2025. The threshold at which contributions start decreases from £9,100 per annum to £5,000 per annum, and the rate increases to 15% (from 13.8%).

3. The potential tax savings by taking dividends rather than salary have been greatly eroded due to:

• the four-percentage point reduction in the main rate of employees’ NICs that has happened (in two phases) from January 2024; and

• the effective increase of about 8.75% in dividend tax rates, which began with George Osborne’s abolition of the dividend tax credit system in 2016; dividends, of course, are not deductible for corporation tax purposes, unlike salary.

The practical impact For the owner of an owner-managed business (OMB), the exact tax cost of withdrawing profits from a company will depend on several factors, including how it is done (dividend or salary, or perhaps interest or rents), what other income you have, the availability of the employment allowance to mitigate employers’ NICs and the company’s level of profits.

The table below is based on the following assumptions:

• The employment allowance is not available (e.g., it is a sole director company).

• The owner has no other income.

• A salary equal to the personal allowance is taken, with the post-corporation tax profits being fully distributed.

The table also gives figures for a sole trader with equivalent profits.

Profit (£) income for director (£) income for sole trader (£)

30,000 24,657 25,468

80,000 56,804 57,711

150,000 87,178 92,040

As you can see, the sole trader is better off at each profit level. Of course, the director would not need to make a full distribution of profits, but many, particularly at lower profit levels, may need to do so. It is worth adding that there seems to be little likelihood of personal tax rates being cut soon, so delaying distributions until later years may not save much tax anyway.

Disincorporation

Some OMBs may want to consider disincorporation. There are no special reliefs when disincorporating, so how this is done will need careful consideration.

Practical tip

Many OMBs should consider whether a limited company is still the most appropriate structure for their business.

Tax deductions for businesses: Is the remuneration ‘excessive’?

When HMRC may deem a director’s remuneration as being ‘excessive’, denying deduction against corporation tax profits.

On the face of it, directors are free to vote on their remuneration as the board sees fit. However, directors should be aware that HMRC may challenge excessive salaries and benefits-in-kind on the basis that they are not ‘wholly and exclusively’ paid for the purposes of the trade.

Open to challenge?

HMRC is less likely to challenge the remuneration of a sole director ‘...where the controlling director is also the person whose work generates the company’s income then the level of the remuneration package is a commercial decision and it is unlikely that there will be a non-trade purpose for the level of the remuneration package’ (see HMRC’s Business Income Manual at BIM47106).

Where a challenge is more likely is where payment is made to other directors (or an employee who is a close relative or friend of the controlling director, including a minor child) under the ‘settlements’ anti-avoidance legislation (ITTOIA 2005, s 619 et seq.), taxing the remuneration as if it were that of the controlling director. Paying wages to a spouse or close relative is acceptable if undertaken correctly with payments being fair, for real work, and being well-documented.

In addition, if a director is remunerated far above what would be considered usual for their role in a similar company (e.g., the work performed does not justify the high level of remuneration) or appears disproportionate to the financial position of the company, this can indicate the existence of a non-trade purpose and may be deemed excessive. HMRC is particularly vigilant if a director’s salary appears disproportionate to the company’s earnings or if there is no corresponding increase in the company’s profitability, especially where the company is loss-making or has very low profits. If a company is not profitable, excessive remuneration could be seen as a method to extract money from the company as part of a scheme to avoid taxes by reducing the company’s taxable profits artificially or avoiding higher rates of tax and NICs.

HMRC can also look at previous years’ declared remuneration and compare year on year, as in Earlspring Properties Ltd v Guest (1995), 67 TC 259. In that case, remuneration paid to the company director’s wife was increased from £1,000 before their marriage to sums varying between £21,359 and £38,777. The company also paid £20,000 or £21,000, respectively as an annual contribution to a pension fund. Paying higher remuneration enabled the large premiums to be paid. The court held that the payments were not ‘wholly and exclusively’ for the company’s trade but represented a diversion of income for fiscal advantage.

Tax implications

If HMRC consider that excessive remuneration has been paid, they can potentially charge the employee to PAYE tax and NICs and the employer to secondary NICs but refuse corporation tax relief on the payment against business profit. Generally, the ‘excess’ is disallowed, with any justifiable amount being deductible.

Where the payment is deemed excessive and the recipient is also a shareholder, HMRC may treat the payment as a distribution of profits – effectively as a dividend, taxed at dividend rates.

Other shareholders

Directors should be aware that payment of excessive remuneration to directors can amount to unfairly prejudicial conduct towards other shareholders. Such a legal challenge by those shareholders is more likely where profits are available for distribution, but are taken by the directors for themselves.

Practical tip

Proper documentation and justification for director remuneration are essential. If the company can provide evidence that the remuneration is reasonable and in line with its financial position, industry standards, and the director’s duties, it may be more likely to withstand scrutiny from HMRC.

Valuing gifts of land and property for IHT

Valuations of assets for inheritance tax (IHT) purposes is a specialised area. It is generally not an area for inexperienced taxpayers or tax professionals to dabble in. Even HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) does not normally engage in tax valuations of assets; instead, it uses specialists in other government departments (e.g., Shares and Assets Valuation for unquoted shares, and Valuation Office Agency (VOA) for land and buildings). Tricky IHT valuation issues potentially include ‘related property’ (e.g., involving spouses), and valuation discounts for jointly owned property. However, this article focuses on land and buildings owned by a single individual (e.g., where a property was wholly owned by a widow on their death).

Leave it to the professionals!

Unfortunately, the IHT legislation offers little guidance on how to determine the market value of transfers. The general rule bases market value around the price that property might reasonably be expected to fetch if sold in the open market at that time. HMRC regards valuations as a ‘high risk’ area in terms of the potential loss of IHT where valuations are too low. Obtaining professional valuations of land and buildings is not compulsory. However, simply guessing market values is not recommended; aside from additional IHT and interest, material undervaluations of property may result in penalties being charged.

HMRC has published an ‘IHT toolkit’ for tax agents or advisers (www.gov.uk/government/publications/ hmrc-inheritance-tax-toolkit). HMRC states that for assets with a material value, taxpayers are ‘strongly advised to instruct a qualified independent valuer, to make sure the valuation is made for the purposes of the relevant legislation, and for houses, land and buildings, it meets Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) or equivalent standards.’ HMRC expects the person seeking the professional valuation to explain the context and draw attention to the definition of market value (in IHTA 1984, s 160), and to provide the valuer with any relevant information and documentation concerning the property.

Latest ‘developments’

A particular difficulty in property valuations can be ascertaining a property’s ‘development value’ (i.e., broadly any increase in value attributable to the prospect of development). When valuing a property, HMRC expects the valuer to consider whether there is any potential for development and, if so, to ensure it is taken into account and reflected in the valuation. HMRC states (in its Inheritance Tax Manual at IHTM36275) that it considers ‘hope’ value to be ‘a component part of the open market value in appropriate cases, whether or not planning permission has been sought or granted’.

The difficulty in establishing development value has resulted in several cases coming before the land tribunal. For example, in Prosser v IRC (DET/1/2000 [2001] RVR 170, the garden of a house was large enough to potentially constitute a building plot. The district valuer suggested a figure as at the date of death assuming planning permission, and deducted an allowance of 20% to reflect that no planning permission had been given at the valuation date. However, the land tribunal held that there was a 50% chance of obtaining planning permission, and that a speculator purchaser in the absence of the planning permission would not offer 80% of the development value, but would only offer 25%. Other notable valuation cases include Palliser v Revenue and Customs [2018] UKUT 71 (LC), and Foster v Revenue and Customs [2019] UKUT 251 (LC).

Practical tip

Useful information on the VOA’s approach to its valuation work for IHT purposes is in its own Inheritance Tax Manual (www.gov.uk/guidance/inheritance-tax-manual)

Incorporation relief uncertainty

A look at some of the finer points of CGT incorporation relief for property businesses.

Incorporation relief for capital gains tax (CGT) purposes is potentially available under TCGA 1992, s 162; broadly, the business owners transfer their interest in a qualifying business, in exchange for new shares issued by the company. On a qualifying transfer, the capital gain that would otherwise arise on the disposal of the chargeable assets is postponed (or ‘rolled over’) into the shares, pending their subsequent disposal, etc.

Where a business transfer qualifies, there is no need for a claim; the relief applies automatically (although it can be actively disclaimed under TCGA 1992, s 162A).

Generally speaking, most of the effort involved in making a successful claim has tended to orient around three key aspects:

1. Does the activity qualify as a business?

2. Have all the assets comprised in that business been transferred to the company?

3. Is any restriction required in terms of the gain that may be postponed?

This article looks at these themes, but also some of the finer points that may be of interest to those undertaking incorporations.

Is it a business?

This part of the path is fairly well-trodden, particularly in the context of rental properties, and thanks largely to Ramsay v HMRC [2013] UKUT 0226 (TCC). The ‘trap’ here is familiarity; people instinctively follow income tax law and its everyday treatment, which broadly describes all income from property as arising from ‘a property business’ (at the beginning of ITTOIA 2005, Pt 3) but does not actually stipulate that all rents from property amount to a business in the wider sense (as might then apply to, say, CGT).

HMRC’s position is partly set out in its Capital Gains Manual at CG65715, although I find its insistence that a landlord spend at least 20 hours a week on the letting activity as some sort of minimum threshold to qualify as a ‘business’ to be a quite simplistic interpretation of the Ramsay case, and some way from the spirit of, say, Griffiths v Jackson [1982] 56 TC 583 and Salisbury House Estate Ltd v Fry [1930] 15 TC 266, notwithstanding the niceties of American Leaf Blending v Director-General of Inland Revenue [1978] 3 All ER 1185, that HMRC seems to prefer.

HMRC also seems to dislike where the letting activity is delegated to an agent (e.g., a property management or letting agency), although this, too, is questionable. For example, HMRC would typically be perfectly happy to find that a taxpayer using an agent was ‘in business on their own account’ in a trading scenario.

Have ALL the assets been transferred?

The legislation at TCGA 1992, s 162 requires that the business be transferred as a going concern and that all business assets be transferred ‘other than cash’; HMRC states at CG65710 that this means everything that is an asset, except for cash and sums held on bank deposit or current account. Notably, this goes beyond simply the ‘chargeable assets’ that will trigger CGT, such as property, and includes goodwill even if it has not been included on the balance sheet to date (it would comprise part of the business as a ‘going concern’, regardless).

But what of assets that a business owner might want to keep personally – or does not want to ‘lock up’ in their new company?

It is understood that HMRC generally applies this rule quite strictly, in particular so that cherished assets may not be retained or ‘held back’ in personal ownership. But this should not prevent the landlord from disposing of some assets naturally in the run-up to incorporation, so long as the remaining business is still counted as a ‘going concern’, able to stand on its own two feet in the commercial sense.

Finer points on ‘all the assets’

There has been some discussion in the professional press recently over whether or not HMRC’s approach is too rigid (or whether some advisers’ approach might have been too lax), and the Chartered Institute of Taxation has even written to HMRC (in late 2024) for clarification on whether HMRC should object to:

1. the landlord retaining debtors as well as cash – perhaps to be able to settle residual liabilities;

2. the landlord retaining the freehold in properties and granting a leasehold to the company on incorporation; or

3. the landlord being able to retain the legal title to the properties being transferred while the beneficial interest is passed to the company.

For instance, it is not difficult to see where a landlord might own the freehold in a mixed-use property but let out only the residential part; having to transfer the freehold might effectively require the landlord to transfer ‘more’ than is actually being used in the letting business. If we work on the basis that the key aim in the statute is to ensure the transfer comprises a viable business, it is also difficult to see why HMRC might insist on the transfer of legal title as well as beneficial ownership (at least to the extent of England and Wales; Scotland has its own peculiar rules in relation to ‘ownership’ – although it would no doubt argue that it is England and Wales who are peculiar!).

What about the business liabilities? Incorporation relief is granted on the basis that the company is offering (new) shares in itself in consideration for the valuable business. It follows that if the company offers cash, or any other nonshare consideration, this restricts the relief.

In the past, HMRC argued that the company’s taking on some or all of the business’s liabilities amounted to such non-share consideration, but this was put right by Extra-Statutory Concession (ESC) D32, which permitted the company to ‘take over’ some or all of the business’s liabilities without it counting as consideration alongside the shares – although it does still speak to the value of those shares.